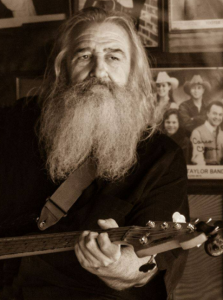

“He looked like a character out of The Hobbit,” said songwriter Bob Regan of his old friend and bandmate Greg Humphrey. That is as good a place as any to start when talking about one of the most colorful and beloved characters in Nashville music history. Hump, as he was known to many, died last Thursday at his home in Green Hills of an apparent heart attack. He was 63.

“He looked like a character out of The Hobbit,” said songwriter Bob Regan of his old friend and bandmate Greg Humphrey. That is as good a place as any to start when talking about one of the most colorful and beloved characters in Nashville music history. Hump, as he was known to many, died last Thursday at his home in Green Hills of an apparent heart attack. He was 63.

The image is perfectly in keeping with his role for much of the past dozen years as bandleader, bass player, talent scout and all-around musical catalyst for Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, Rippy’s and Honky Tonk Central. For literally hundreds of young singers and players who have flocked to the city through its vibrant honky-tonk portal on Lower Broad, Humphrey was often ringmaster, gatekeeper, counselor, encourager, mentor, friend and shoulder, all in one eternally rumpled package.

Behind that role was a truly impressive musical background. Jimmy Snyder, whose band he played with in Northern California in the ’70s, made him part of the house band at the legendary Palomino nightclub in North Hollywood, the Palomino Riders, named the Academy of Country Music’s Best Non-Touring Country Band in 1980. When Snyder let him go — punctuality was never a Humphrey strong suit — “he pulled out his phone book and put together The Shutouts,” according to Regan. A cross-pollinated all-star ensemble containing members of The Band, The Flying Burrito Brothers and the bands of Roger Miller and Crosby Stills & Nash, it featured Greg’s then-wife Rosalie North, Regan, Dave Fraser, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, Thumbs Carllile, Dallas Taylor and Garth Hudson.

His ability to bridge musical gaps came from his love of both rock and country.

“He was one of the first generation of dope-smoking country musicians,” says Regan, “but he was able to bring in the guys from the ’40s and ’50s. He had an encyclopedic musical knowledge. You could not stump him. You could call any song in any era, and if it had anything to do with country music, he would play it flawlessly and probably knew the words too.”

The list of those Humphrey worked with as sideman, session player, engineer or producer includes Willie Nelson, Albert Lee, Townes Van Zandt, Mickey Newbury, The Everly Brothers, Johnny Lee and Jo-El Sonnier, as well as hundreds he opened for in various house bands. He worked with Cowboy Jack Clement, wrote with Warren Haynes, and co-wrote (with Michael Smotherman) “You’re My Angel,” on Brooks & Dunn’s If You See Her album. He also spent several years working in publishing on Music Row.

His journey wasn’t always a smooth one. Economic necessity took him at first to Tootsie’s, where he again worked with Snyder, but he embraced the role and became a one-man Welcome Wagon. Working with Tootsie’s entertainment director John Taylor, he kept musicians on every stage in all three clubs day and night seven days a week.

“I would stop in to have coffee with him at his house,” says Silvertone Recording Studio owner Jack Irwin, “and he’d be sitting in his room juggling a hundred musicians, their talents and egos. It was a marvel to behold. It was like watching somebody with a Rubik’s Cube, but he made it look effortless.”

Those musicians — veterans and newbies — gathered Saturday at the weekly back-room open mic Humphrey hosted at Tootsie’s, singing, crying and reminiscing.

“He’d find a place for you to do something so you could get your feet wet the first week you moved in and found Lower Broad,” says guitarist Eugene Moles, whose résumé includes work with Merle Haggard, Buck Owens and the Opry house band. “There’s nobody down there like that. He was like that with me when I was a teenager, and all the way up until he died he was doing that for young people.”

He was patient with raw talent, and he could work with the schooled. Taylor says, “One of my best fiddle players told me once, ‘I didn’t know how to play fiddle until Greg taught me. I only knew how to play a violin.”

Crystal Shawanda, a Canadian artist who went from Lower Broad to an RCA deal, first came to Nashville at 12.

“He was in the first band I sat in with at Skull’s Rainbow Room in Printers Alley, and then he was over at Tootsie’s,” she says. “He was so good at remembering names, and he made everyone feel important. He made you feel like you fit in somewhere, like you belonged. I think that’s why he loved Nashville so much, because it gave him a place where he made sense, where people like us make sense.”

Humphrey introduced Shawanda to her husband Dewayne Strobel, and he was an equally adept musical matchmaker with a great sense of loyalty.

“We started working together in 1997,” says Irwin, “and honestly, he probably brought in 50 percent of the work in my studio during that time. He was continually bringing newbies from downtown either to do guitar/vocal demos or for writing sessions or full-blown records.”

Humphrey led the house band at Tootsie’s 50th anniversary party at the Ryman in 2010, backing Kris Kristofferson, Mel Tillis, Jimmy Dickens, Jamey Johnson, Terri Clark, Lorrie Morgan, Mark Chesnutt, Randy Houser and many others. He was seen backing Keith Urban on Tootsie’s main stage recently during an episode of this year’s American Idol.

The tone of the memories on Lower Broad, on Facebook and in phone conversations is overwhelmingly loving. For all his faults, self-sabotage sometimes among them, he was difficult to dislike, even by people — and there were many — he owed money.

“I’d think, I know Greg’s working me,” says Regan, “but he’s so good at it I’m just going to go with it.”

“Even if he didn’t have anything, he would borrow money from me to give to someone who needed it more,” says songwriter Pebe Sebert, who was so close to Humphrey for a time that his children call her “an honorary spouse.” Sebert’s own children, including singer Kesha, saw the ever-present Humphrey as a stepdad. They also saw his reach.

“I had moved and gotten divorced and spaced out and was owed a bunch of royalties I didn’t know I was supposed to be getting for ‘Old Flames Can’t Hold a Candle to You,” says Sebert. “When I figured it out, I talked to people in Nashville who said, ‘Well, too bad for you after so long.’ But Humphrey said, ‘Let me make a phone call,’ and a few months later I got a big check in the mail.

“And we were in New York once and my son loved baseball and we didn’t have a lot of money, and Greg knew the guy who was umpiring the Mets game that afternoon and got us in. Then he called the head of BMI, who took us to the Russian Tea Room.”

He was, at heart, a lover and an encourager.

“I don’t know if I’d have survived without Humphrey,” says Sebert. “I was in a really low place. I had a record deal and a publishing deal that went away, I’d been on welfare, and then my mom, who had been my only supporter, died. I was waiting on people I’d helped get their start and cleaning their houses. Talk about being humbled. But Humphrey probably saved my life and my kids’ lives. I don’t know if Kesha’d be a star if it weren’t for him, because I don’t know that we could have stayed here. Things weren’t good. But once Humphrey came into the picture, he just made everything okay. He knew I was a basket case, and he kind of put me back together. I owe him a lot.”

“His favorite movie was It’s a Wonderful Life,” says Irwin, “and if you try to imagine this town without Greg having been in it, it’s like imagining Bedford Falls without Jimmy Stewart. It would be a completely different place.”

A service will be held 10 a.m. Thursday, Jan. 22, in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford Theatre. Humphrey is survived by three daughters, Rocky, Emily and Sarah, by seven grandchildren, one great-grandchild, and countless young musicians he welcomed, encouraged, tutored and loved.

Recent Comments